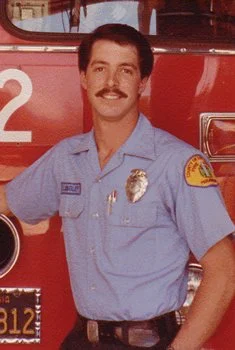

Jeffery Langley

Memory of FFPM Jeff Langley, Killed in the Line of Duty, Lives On.

By Larry Collins

20 years ago last month, FFPM Jeff Langley lost his life at a technical rescue in Topanga Creek State Park. Jeff left a worldwide legacy that continues to this day, including an international award that bears his name. On March 28, the Los Angeles County Fire Department honored Jeff’s contributions at a 20-year commemoration ceremony at the Pacoima Facility, in front of a Department training site that bears his name.

The Higgins & Langley Memorial Awards were established after Jeff’s death in 1993 by the National Association for Search and Rescue Swiftwater Rescue Committee. The awards are co-named for Langley and for Earl Higgins, a writer and filmmaker, who lost his life in 1980 while rescuing a child who was swept down the Los Angeles River.

The Higgins & Langley Memorial and Education Fund (a nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing the cause of safer and more effective swiftwater rescue operations) has increased awareness about the need for effective swiftwater and flood rescue training, planning, procedures, public education, and preparedness in fire departments and other public safety agencies. The awards have helped inspire public safety agencies across the nation and around the world to develop viable water rescue programs to protect the public and rescuers alike. It is a fitting tribute to a member of our Department who was so dedicated to improving the safety of his own colleagues and of the people we serve.

Langley was an enthusiastic participant in our Department’s early efforts to establish swiftwater rescue capabilities. He helped conduct testing of new procedures, became a swiftwater rescue instructor, and trained many of our personnel how to stay alive during swiftwater emergencies. After disastrous floods struck Southern California in 1992 and 1993, he was part of the group of L.A. County Fire Department personnel who pioneered the development of new “Helo-Swiftwater Rescue” procedures and equipment now being used around the world. Jeff also participated in some of the early USAR program developments and implementation efforts, and he excelled as a model Air Operations firefighter/ paramedic and as a person.

The emergency that took Jeff’s his life began when a teenager fell 150 vertical feet off the face of Eagle Rock, a huge monolithic stone in Topanga Creek State Park. Jeff was assigned to the copter that was dispatched with Fire Station 69, Truck 125, USAR-1, and Battalion 5 to the remote site. The copter arrived first and engaged in the rescue. The rest, as they say, is history.

Jeff’s fatal fall has yet to be fully understood to this day, and because of the circumstances of the event only he will ever know exactly what happened. A number of new safety procedures were adopted in the wake of this accident, which has increased the safety for Air Ops personnel and for other Department members engaging in copter-based rescue operations. Some felt that they were guided by Jeff’s hand as these procedures were developed, adopted, and implemented. That would not be a surprise to those who knew him.

Jeff never got the chance to deploy to help people around the United States and around the world with his colleagues on the Department’s USAR Task Force, CA-TF2. But he squeezed a lot of living into 28 years and saved many lives directly and indirectly. His spirit lives on every time our Department rolls out the door to help someone in trouble here in L.A. County and everywhere we go.

Today, Jeff’s likeness graces a memorial named “The Aviator”, a sculpture crafted of stone hand-quarried from the mountains in Santa Barbara County and hand-chiseled by renowned artist John Cody as a gift to our Department and as a remembrance to Langley. The names of Jeff and of Pilot Tom Grady (who lost his life in a tragic copter collision at a brush fire in the 1970’s) are etched into the marker.

The iconic monument graces the base of the Air Ops Training Tower named for Jeff at the Pacoima Facility. So in a way, Jeff Langley is still there every day, wishing safe flight to every helicopter that lifts off or lands at Barton Heliport; and he’s there to send off the Heavy Equipment units to wildland fires and other emergencies, and he watches as CA-TF2 personnel assemble and deploy to disasters wherever they occur.

See an image of the Sculpture

https://fire.lacounty.gov/the-aviator-sculpture-re-dedicated-on-anniversary-of-ffpm-langleys-death/

A Cross Hangs In the Sky

By Al Martinez

The following was published in the Los Angeles Times just a few days after Jeff Langley’s death. The author is venerable Times columnist Al Martinez, a longtime Fire Department supporter and Topanga Canyon resident who actually saw the copter pass over his home and watched Jeff standing on the skids of the copter as it approached the cliff rescue that took his life in Topanga Creek State Park.

He was like a crucifix hanging in the sky, arms outstretched on each side as he clung to the doorway of a helicopter, feet planted on its skids, looking off to the distance.

I can see him now against the pale blue of a late afternoon, just over the tops of oak trees that grow in clusters down the hill from my home. Though the helicopter hovered for perhaps only 30 seconds, the image is difficult to forget amid the circumstances that surround it. I’ve been trying to shake it for a month.

The aircraft belonged to the L.A. County Fire Department on a rescue mission. The man in the doorway whose posture appeared so cross-like was Jeff Langley, a (fire fighter) paramedic.

A few moments after I saw him he was dead.

The incident occurred on a quiet Tuesday in the Santa Monica Mountains, a few miles from where I live. A young man, out of breath from running, asked me to call 911. A climber had fallen off a steep cliff in Topanga Creek State Park. Almost simultaneously, we heard the roar of a helicopter. The aircraft appeared from the west, hovered momentarily and was gone. It was during that brief view of the chopper that I saw the man in the doorway.

As it turned out, the climber they had airlifted from the foot of a 150-foot cliff had died in the fall. The helicopter had returned to recover equipment left at the scene. Exactly what happened next might never be known. One moment Langley stood in the doorway of the chopper as it hovered over a canyon, and the next moment he was gone. They found his body in under-brush not far from where the climber had fallen.

News of his death left an unsettling memory of the scene. Paramedics aren’t supposed to die. They’re life-givers, savers, last resorts in moments of pain, fire and tangled debris. We see them hurtling down the freeways and across the canyons of L.A., or overhead in helicopters, chasing the seconds that will bring them to the place where life forces flicker.

They are not supposed to appear Christ-like in the sky and then plunge to their deaths moments later. I say that from the standpoint of one who admires them. They work 56-hour weeks under circumstances that would easily tax the resolve of those not similarly committed to saving lives.

Whenever disaster strikes, you can count on a paramedic being there, pressing the limits of safety and endurance to stem the flow of blood or restart a silent heart; to deliver a baby or to breathe life back into a strangled child.